Winchester’s early businesses

Published 11:26 am Friday, March 3, 2017

Our town was established by an act of the General Assembly on Dec. 19, 1793. Turn-of-the-century Winchester still reflected the wilderness character of the surrounding area. Pioneers recalled that the streets were cut out through thick canebrakes.

There were only six streets in the original town plan. Running generally north-south were Water, Main and Highland; those running east-west were Washington, Main Cross and Fairfax. None were paved. Dirt streets were crisscrossed by forks of Town Branch, which caused problems for years. Bridges had to be built and maintained to allow passage of wagons. This stream still flows but has been channeled underground.

The first courthouse, completed in 1794, was a log cabin. It was replaced in 1797 by a two-story brick structure. Other public facilities included a jail, market house, stray pen and public spring.

By 1809-10, Winchester had six taverns licensed by the county court: John Martin, Ann Smith, Edmund Callaway, Peter Flanagan, Mordecai Gist and Amon Cast. There was plenty to drink — the county had 44 distilleries in 1810. Anyone could make whiskey; however, one could be fined for “retailing spirituous liquor without a license.”

At this time, the town had a post office, hotel (National House), Masonic lodge, school (Winchester Academy, usually called the “Seminary”), a state-chartered library company and a branch of the Bank of Kentucky.

Businesses identified from early deeds include a ropewalk, brickyard, slaughterhouse, livery stable, saddler shop, two cabinet shops, two tanneries, two tailors, several bootmakers, several doctors and attorneys, a wool-carding factory and a blue dyer.

In the 1812-15 timeframe, John Ridgway, Philip B. Winn, William N. Lane, George Kennedy, Joseph Coulter, George Webb, James Dunnica, Thomas Barbee, William Hickman and Thomas R. Moore had brick houses, which were combination businesses and residences.

A local newspaper, The Winchester Advertiser, made its debut in 1814. Its office was in “the brick building nearly opposite the Post Office.” Advertisers used the pages to hawk their wares.

There were nearly two dozen merchants who sold a surprising variety of goods. Most of the merchandise came from back east and required a grueling journey to transport to Kentucky. Most Winchester merchants made at least two trips each year to Philadelphia to acquire their goods.

James Anderson used the newspaper to cajole his customers to pay their bills: “Please settle accounts, as we wish to start to Philadelphia in February for a fresh stock of goods.”

A merchant first had to travel to Pittsburgh, by land or water, over the mountains then east to Philadelphia. Buyers purchased goods from wholesalers, packed them onto wagons and drove them over the mountains to near Pittsburgh. Goods were put onto flatboats, usually at Redstone (now Brownsville) on the Monongahela River. Boats floated down the Ohio River to Limestone (now Maysville), where merchandise was again loaded on wagons. The last part of the journey was along the road from Maysville to Lexington on the old buffalo trace (now US 68). A few miles past Lower Blue Licks, they turned off onto Strode’s Road, which ran south to near Winchester.

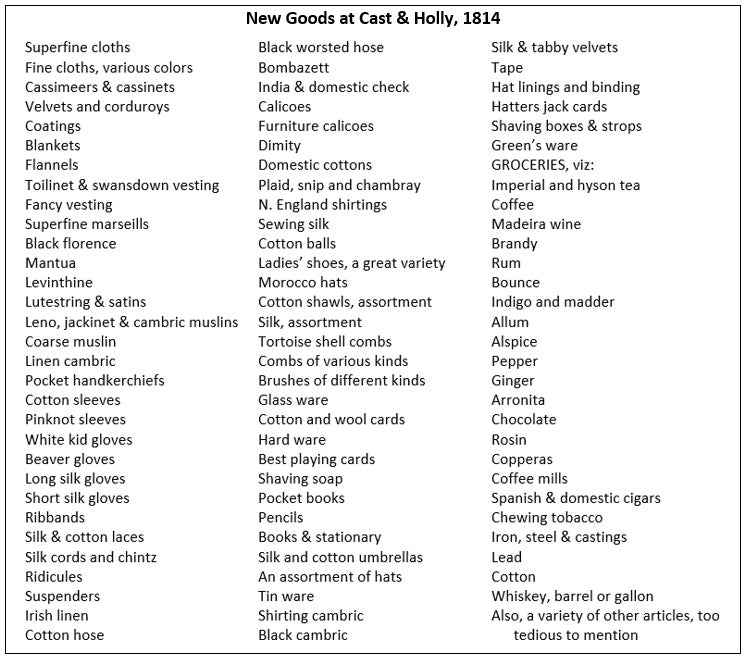

As mentioned above, Winchester merchants stocked a wide array of goods. The sample shown here is from Cast & Holly’s 1814 advertisement: “New Goods, Cast & Holly. Have just received and are now opening in the house formerly occupied by Amon Cast, a large and elegant assortment of Merchandise, consisting in part of the following articles, viz….”

My first impression after looking over the list was “Wow! What an amazing assortment of items for such a small town.” Winchester at that time had fewer than 50 families. The store carried an especially wide selection of fabrics and other materials for homemakers to fashion into clothing.

On closer inspection, there were numerous items that I had no idea of their meaning. I have heard of “dimity,” for example, but could not describe it. According to Wikipedia, dimity is “a lightweight, sheer cotton fabric, historically employed for bed upholstery and curtains, and usually white, though sometimes a pattern is printed on it in colors.”

One I particularly liked was “ridicule.” Turns out, this was a variation on the spelling of “reticule.” This was a small drawstring purse that women carried in the 18th century when dresses no longer had pockets and that eventually evolved into a fashion accessory.

Other items sent me to Webster’s Unabridged and the Oxford English Dictionary. “Marseilles” is a thick cotton fabric; “black florence,” a fancy lace; “lutestring,” a glossy silk material resembling satin; “cassimere,” a soft, twilled woolen fabric now called cashmere; “cassinette,” a thin cloth with a cotton warp and a weft of wool. “Toilinet” is a fine cloth with silk warp and woolen weft, and “swansdown” is a soft, thick fabric of wool with a little silk or cotton; both were used to make fancy waistcoats. In weaving, weft refers to thread which is drawn through at right angles to the lengthwise warp thread. “Bombazett,” or “bombazine,” is a twilled dress material of worsted, often used for mourning clothes.

“Bounce” is a liqueur made by infusing brandy with cherries and sugar. “Copperas” is a mineral of ferrous sulfate used at that time to make ink and dye wool. Interesting that whiskey sold by the gallon or by the barrel. (I was unable to identify “levinthine,” “pinknot sleeves” and “arronita.”)

Based on the goods offered by just one business, it appears our early stores were well stocked for their day and age. Nothing like Walmart or Lowe’s today, of course, but hey, this was more than 200 years ago.