ENOCH: Clark County’s most historic places — Canewood

Published 3:42 pm Thursday, October 15, 2020

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

One of the most remarkable people who ever lived in Clark County was Nathaniel Gist (1733-1796), a name that will not be familiar to many.

He led a life full of adventure, then settled here in 1794, only to pass away several years later.

His homeplace, Canewood, was renowned for its grand opulence as well as its hospitable occupants. Sadly, not a trace of this landmark has survived.

Nathaniel’s father was the well-known explorer, Christopher Gist (1705-1759), who emigrated from England to Maryland. His 1751 journal records one of the earliest European visits to the Bluegrass area of Kentucky.

During the French and Indian War, Christopher served as captain of a scout company in George Washington’s Virginia Regiment. His son, Nathaniel, was a lieutenant in the company. Both father and son were present at Braddock’s Defeat in 1755.

Nathaniel also saw service in the Revolutionary War. Washington appointed him colonel of a regiment in the Continental Army. He led his infantry unit in battles at Brandywine, Germantown, Monmouth and Paulus Hook before being captured in the disastrous Siege of Charleston.

After the war, Nathaniel married Judith Cary Bell, and the couple resided in Buckingham County, Virginia, until removing to Kentucky.

A fellow traveler, who met Gist on the way to Kentucky in the spring of 1793, left this description: “He was a venerable looking man, I should think near 60 years of age; stout-framed and about six feet high and of a dark complexion.”

That summer, Nathaniel hired James Bristow of Bourbon County to build a home for his family. The detailed contract called for a two-story, nine-room frame house with 12-foot ceilings and 24 windows to be finished by the following May. Bristow received 150 pounds of Virginia currency in payment.

Gist held two 3,000-acre tracts of land awarded for service in the French and Indian War. Both tracts were situated on Gist’s Creek, now called Stoner, and were located in Bourbon County at the time. (That part of Bourbon was awarded to Clark County in 1798.)

Nathaniel sold off all but 2,000 acres, where he built his home about six miles north of Winchester.

These cane lands, covered in Kentucky’s native bamboo, Arundinaria gigantea, contained some of the finest soils in the Bluegrass.

Judge James Flanagan, Winchester’s early historian, penned a history of the Gist family and described their homeplace: “Canewood was the seat of refinement and hospitality, the ideal country home of the olden time. The writer was at Canewood in 1841, but time had wrought her vengeance…. The primeval house was surrounded by yards and grounds as lovely as nature in her prodigality could make them, and he remembers no spot upon the earth that has since looked more beautiful.”

According to the late Kathryn Owen, Nathaniel died in 1796, after a residence here of little more than two years. He was buried in the family graveyard, since destroyed.

Multiple alternative dates have been reported, which one source summed up as follows: “Interestingly, historians cannot seem to agree on when Gist died or where he was buried, though most believe he passed away in 1812.”

County court records indicate otherwise: Judith Gist and John Breckinridge were appointed administrators “of the estate of Nathaniel Gist, deceased,” in June 1797, giving credence to the earlier date. This also suggests that historians often fail to consult local sources.

Judith would remarry in 1807, hardly possible if Nathaniel were still living. Her second husband was Gen. Charles Scott, a distinguished soldier of the Revolutionary War.

Scott would be elected governor of Kentucky while residing at Canewood.

Judith died during the cholera epidemic of 1833.

Nathaniel and Judith reared a talented family with “five handsome and dashing daughters.” Daughter Sarah married Jesse Bledsoe, one of Kentucky’s ablest lawyers and a U.S. Senator. Daughter Anne married Dr. Joseph Boswell, a Fayette County physician; their daughter married Gov. Luke Blackburn. Daughter Eliza married Francis Preston Blair of Frankfort, who later became editor of the Washington Globe; their son Montgomery was President Lincoln’s Postmaster General. Daughter Maria married Benjamin Gratz, a wealthy merchant and civic leader in Lexington; their home, Mount Hope, is still standing beside Gratz Park.

Maria and Benjamin were the last of the family with ties to Canewood. They sold the house and farm to Matthew Hume in 1853. The house burned a few years later.

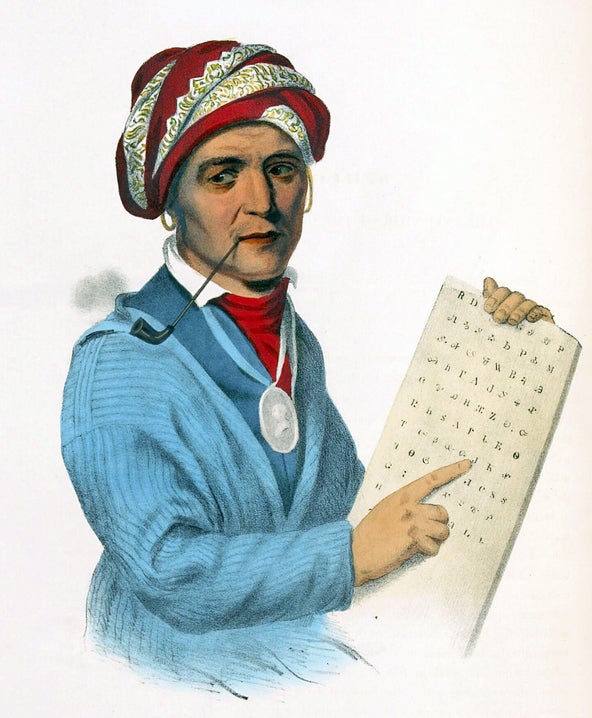

There is one more reason to know Nathaniel Gist. He is the reputed father of Sequoyah, that most illustrious member of the Cherokee Nation. He is credited with a singular accomplishment: creation of the first Native American writing system. He has been remembered with a U.S. postage stamp, the scientific name of the giant redwood trees, Sequoia sempervirens and many other honors.

Sequoyah’s mother was Wut-teh, a full-blooded Cherokee. No one has provided proof positive of his father. One legend has it that Gist was trading with the Native Americans in North Carolina where he “married” Wut-teh. Sequoyah’s birth in the 1770s is thought to have occurred after Gist returned to Virginia to join Washington’s army.

There are several lines of evidence suggesting the legend may be true.

First, Sequoyah was known to whites as George Gist or George Guess, and there is documentation showing that Nathaniel Gist spent considerable time as a trader among the Cherokee.

Finally, John Mason Brown, Louisville lawyer, author and Nathaniel Gist descendant, stated that Sequoyah visited the Gist family in Clark County. Another descendant stated that Howard Gratz “told me that his grandfather, Nathaniel Gist, was the father of Sequoyah. He added that he had met Sequoyah in boyhood, that Sequoyah had stopped off and visited the family on their plantation while on a trip through Kentucky.”

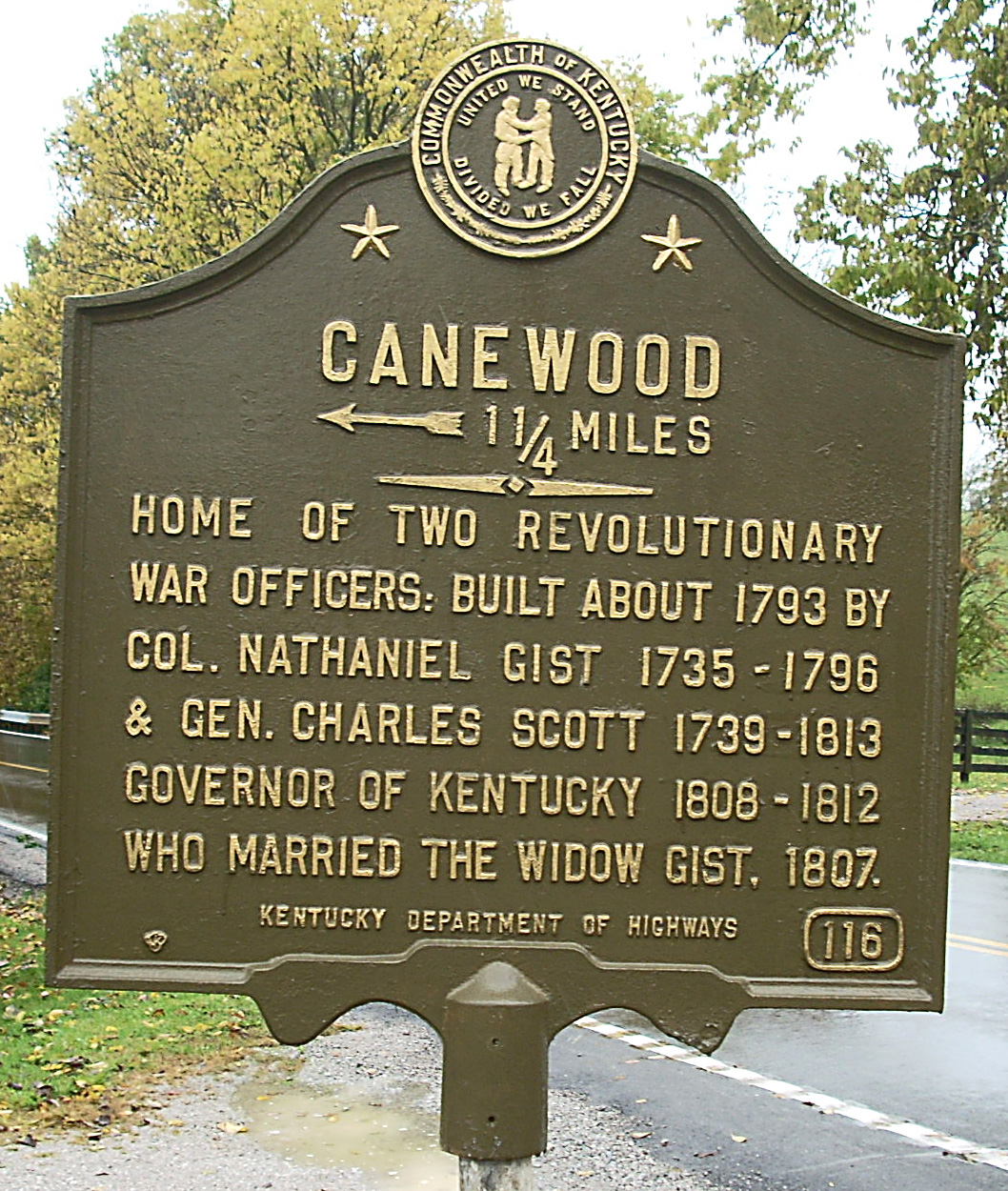

While Nathaniel Gist left only a small footprint in Clark County, he and his family made their mark in American history. All that we have to commemorate their presence today is a Kentucky highway marker.

Harry Enoch, retired biochemist and history enthusiast, has been writing for the Sun since 2005. He can be reached at henoch1945@gmail.com.