Where in the World: Winchester heroes at Santiago

Published 10:00 am Friday, July 3, 2020

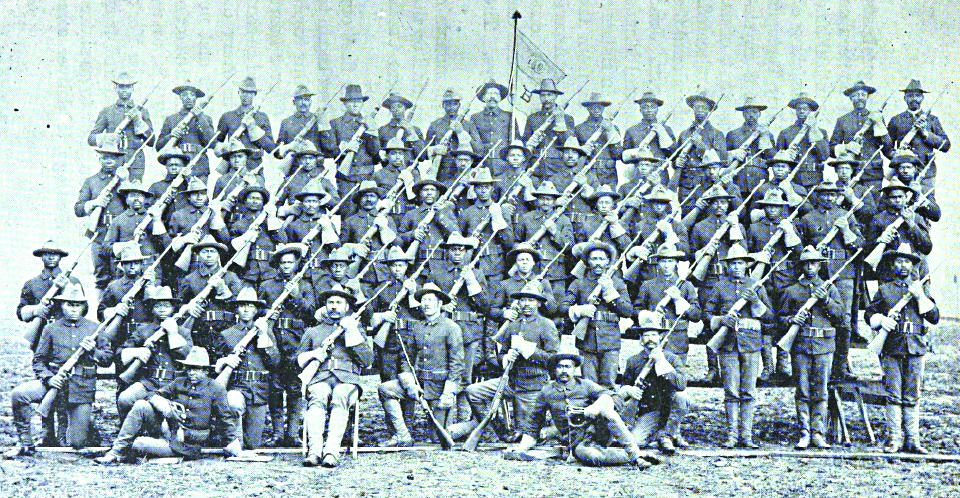

- Thomas Berry’s unit, Troop B, Tenth Cavalry, shown prior to embarking for Cuba. (Photo submitted)

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Harry Enoch

The Winchester Democrat of Oct. 11, 1898, carried an article about local servicemen in Cuba during the Spanish-American War.

“‘Smoked Yankees’ was the name given to the colored troopers who fought so gallantly at Santiago. Winchester had several representatives in the ranks of these heroes — James Rogers, Sam Wheeler, Jack Bell and James Watts of the Ninth Cavalry, and Thomas Morton Berry, George Taylor and William Jackson of the Tenth. James Watts was killed, and Berry and Jackson were wounded in storming San Juan Hill.”

Thomas Berry graduated from Oliver Street School with highest honors, and taught school at Ruckerville before enlisting in the Army in February 1898. After several months of training, in June his unit, B Troop of the Tenth Cavalry, embarked at Tampa, destination Cuba. They landed at Daiquiri on the extreme southeastern coast of the island, about 18 miles east of Santiago. Berry described the action to a reporter for the paper.

“The regiment ate an early breakfast and moving forward was joined by the First Cavalry and the Rough Riders and a part of the Twenty-Third Infantry making a force of about one thousand men. Early that morning (June 24th) occurred the fight at Las Guasimas, where young Hamilton Fish was killed, and the Rough Riders were rescued from their perilous position by the charge of the Tenth Cavalry (colored). Berry’s company in this struggle had one man killed and seven wounded. The Spaniards had 1,500 men engaged behind trenches and supported by two machine guns from [Admiral Pascual] Cervera’s fleet. The fight lasted about two and a half hours in a rough, hilly country and under a blazing red hot sun.”

The Tenth was a dismounted cavalry unit with all white officers, one of whom was Lt. John J. Pershing. (This is the same Pershing who commanded the American Expeditionary Forces in World War I.) Pershing described the rescue in his account of the battle. The Rough Riders, having led the way up a ridge, were ambushed and in danger of being annihilated by Spanish sharpshooters, who were firing from under cover and picking them off one by one.

“While the advance of the Rough Riders was in progress the First and Tenth Regiments were moving up the main road to the right. These regular cavalry regiments attacked the Spanish left and drove them from their position in front and occupied it. The Tenth Cavalry having charged up the hill, scarcely firing a shot and being nearest the Rough Riders, opened a disastrous enfilading fire upon the Spanish right, thus relieving the Rough Riders from the volleys that were being poured into them from that part of the Spanish line. This is in brief the story of how the Tenth Cavalry relieved the Rough Riders at Las Guasimas.”

The rescue of the Rough Riders at Las Guasimas by the Tenth Cavalry has been lost in history, completely overshadowed by the Rough Riders’ subsequent charge up San Juan Hill, led by Col. Theodore Roosevelt.

Returning to Berry’s account, he relates how his unit fought side by side with the Rough Riders in the battle for the hill.

“The regiment rested just beyond the battlefield until the night of the 30th, when it took position for the movement on San Juan which began next morning. The roads were narrow and horrible although the engineer corps had improved them considerably. The soldiers carried their rations of bacon, hardtack and coffee and also their ammunition. There were a number of small streams from a foot to a foot and a half deep before they reached San Juan river, which ran at the foot of the hill on which the fort to be stormed was located. The river was up to the armpits of the shorter men and had to be waded.”

On July 1, “Berry’s regiment was in line of battle at about nine o’clock a.m. after having crossed the river. The artillery was posted behind the infantry, which encountered a storm of shells and rifle balls. Berry’s company had sixty men in line, three yards apart. There were no barbed wire cutters on the first day and the soldiers had to break the wires with the butts of their muskets. The battles raged from nine in the morning until 4:45 p.m. Berry received a flesh wound in the hip about 1:30 p.m. as he went up the hill but kept his place in the ranks. About 2:30 p.m. a man in Company G of the Tenth was badly wounded, and Berry had taken him in his arms to help him to where he could be cared for, when a bullet struck the wounded soldier in the forehead, killing him instantly. At half-past four, just as his command was rushing on the fort and victory was assured, Berry was shot in the foot and with a little aid hobbled back to where the ambulance corps took charge of him and carried him to the rear.”

Two days after the victory at San Juan Hill, the U.S. Navy destroyed Admiral Cervera’s fleet, which led the Spanish to sue for peace. Teddy Roosevelt’s remarkable flair for publicity made him the most celebrated participant of the Spanish-American War. Today the only things most people remember about the war are the sinking of the Maine and Roosevelt’s charge up San Juan Hill. However, Roosevelt himself praised the colored regiments.

“The Ninth and Tenth Cavalry Regiments fought one on either side of mine at Santiago, and I wish no better men beside me in battle than these colored troops showed themselves to be. Later on, when I come to write of the campaign, I shall have much to say about them.”

Thomas Berry was sent to a hospital in Georgia to recover from his wounds and malaria and got home on leave in late August. Berry was discharged from the Army in 1901, made Winchester his home and taught in the public schools here until about 1914. He received a military pension for disabilities resulting from the war. The 1920 census shows Thomas was then living in Baltimore with his wife Lula and daughter Roussilon. By the 1930 census, we find Lula, widowed, living in Columbus, Ohio.

Sources:

Edward A. Johnson, History of Negro Soldiers in the Spanish-American War (Raleigh, NC, 1899); Herschel V. Cashin et al., Under Fire With the Tenth U.S. Cavalry (London, New York, Chicago, 1899); Frank Pullen, “A Perfect Hailstorm of Bullets: A Black Sergeant Remembers the Battle of San Juan Hill,” online at http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/100/; Anthony L. Powell, “An Overview: Black Participation in the Spanish-American War,” online at www.spanamwar.com/AfroAmericans.htm; Thomas M. Berry, enlistment records and pension certificate, online at www.fold3.com.

Harry Enoch, retired biochemist and history enthusiast, has been writing for the Sun since 2005. He can be reached at henoch1945@gmail.com.