At the Museum: Mattie Bean’s quilts make a legacy of practical art

Published 8:54 am Monday, February 20, 2017

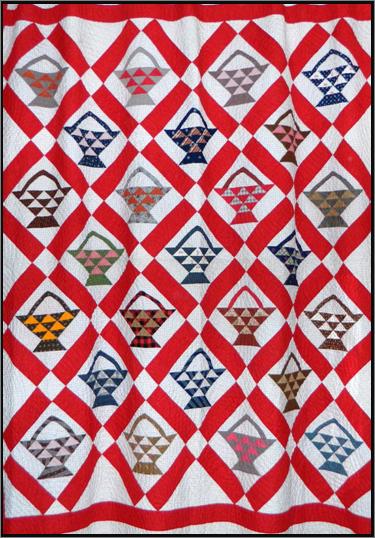

- This basket quilt was sewn by Mattie Bean in 1885. (Photo submitted)

By Rosemary Campbell

Bluegrass Heritage Museum

In the last “At the Museum” column, I wrote about the Bean family collection and some information about the early generations of that family in Clark County. As promised, this article will focus on the lovely and remarkably preserved quilts made by Mattie Bean as she grew and throughout her adulthood.

Mattie Gay Bean was born April 26, 1864, to Edwin P. and Sallie Owen Bean. She lived a long life, dying at age 84 on May 14, 1948. She never married.

When Mattie’s great-niece Martha Hukill Honican willed the Bean family heirlooms to the Bluegrass Heritage Museum, a dozen lovely quilts in nearly pristine condition were included. Mattie signed and dated the two oldest ones, from 1885 and 1897. The rest are unsigned, but Mrs. Honican believed Mattie was involved in the creation of most, if not all, of the quilts.

Many people associate quilting with pioneer times, and this was certainly an important task for women then. However, in creating her quilts Mattie was carrying on a tradition begun thousands of years ago.

In fact, the earliest known piece of quilted clothing was found on an ivory figure of a Pharaoh of the Egyptian First Dynasty from about 3,400 B.C. Knights of the Middle Ages wore quilted clothing under their armor for comfort. People used quilting in clothing, draperies, tapestries and bedding in many parts of the world in early times.

The first reference to quilting in America was in a household inventory in the late 1600s, and the earliest surviving bed quilt is from 1704. According to historians, quilt-making increased in the 19th century between 1825 and 1875, probably as a result of westward expansion. They were used for warmth, of course, and also to cushion and protect items from breaking in the wagons during bumpy rides west.

Mattie belonged to the fourth generation of Beans living in Clark County, so she wasn’t a pioneer herself. But perhaps Mattie learned quilting skills handed down from her own pioneer ancestors.

The earliest of her quilts in the collection is a basket quilt, signed and dated by Mattie in 1885 when she was 21. It hangs in the museum’s second gallery on the first floor. Baskets were a common motif in traditional quilts, as they were used in daily life for many purposes. Many of the oldest quilt patterns reflected everyday items.

The other signed quilt is in the Coxcomb pattern and is dated 1897, when Mattie was 34. This quilt hangs at the head of the second floor hallway. Its intricate stitching shows Mattie’s advanced quilting skills.

One of the most interesting quilts is an elaborate crazy quilt with “1898” embroidered on the front. This quilt is currently hanging in the second floor Williams/Holloway Gallery. It consists of hundreds of irregularly-shaped pieces in a wide variety of fabrics and colors. A few seem to be fairly plain, homespun fabrics, but the majority are plush velvet, silk, satin and brocade, probably left over or repurposed from blouses and gowns. Decorative stitches are embroidered over all the seams; their wide variety suggests that this might have been a friendship quilt, stitched together by a group of women.

The crazy quilt pattern was one of the most popular of the late Victorian period, inspired by Japanese art exhibited at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. The Japanese ceramics on display had asymmetrical designs and a crazed finished, which left a random and somewhat broken appearance in the glaze. American women sought to incorporate this haphazard look in their quilts, but their creations were anything but haphazard as a great deal of planning went into the layout of the various shapes.

Several Bean family quilts date from the 1920s through 1940s, based on the fabric used — feed sacks. During the Depression and World War II, people were coping with financial stresses and frugality was the rule. Nothing was wasted, including the bags that held flour, salt, sugar, etc.

Resourceful women used the sacks to make aprons, curtains, and more. Three sacks could provide enough fabric to make a woman’s dress. Grain producers recognized this and began producing printed feed sacks as a marketing strategy. Much like in earlier pioneer times, quilters carefully saved scraps from old clothing and other textiles to be repurposed and included in their quilts.

These materials did not limit creativity, however. While several of the feed sack quilts in the collection are less ornate and more practical in nature than earlier Victorian counterparts (for example, a pastel crazy quilt and a nine-patch pattern), some are quite intricate and rely on advanced skills (a double wedding ring quilt and a diamond mosaic pattern).

All of the quilts in the collection reflect the quilter’s dedication, skill and love for “playing” with colors and shapes to create beautiful works of practical art. They also reflect the times in which they were created.

If you are interested in seeing Mattie’s quilts for yourself, please don’t delay. They have been on display for a few years now and soon must be taken down and “rested.”