The inspiring career of William Webb Banks

Published 11:47 am Friday, February 3, 2017

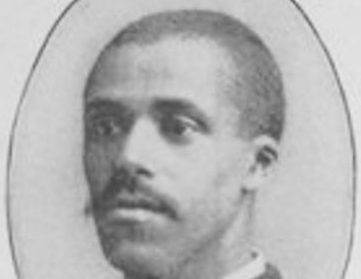

- William Webb Banks (from the Golden Jubilee of the General Association of Colored Baptists in Kentucky, 1915)

Over the past two centuries, our community has produced many noteworthy citizens. Though he is little known today, William Webb Banks (1862-1928) deserves a place in that pantheon.

Banks, born into slavery in Clark County, acquired a college education and achieved statewide acclaim as a journalist and churchman. His death was marked by an unusually lengthy obituary in The Winchester Sun, from which we are able to glean many items of his personal history.

Webb was the son of Paducah Banks and Catherine Martin. His father, though named for the famous Chickasaw chief “Paduke,” usually went by Patrick; he was raised by the Webb family in southwest Clark County. His mother, also known as “Kitty,” was said to have been raised by the Bush family, but records uncovered by researcher Lyndon Comstock indicate she was owned by Elizabeth Baber Field Martin, wife of Robert E. Martin.

Sometime after the Civil War, Patrick moved the family to Winchester where he was a carpenter. In 1868, Patrick and Catherine came to court to declare they had been married for 14 years. This step was necessary since slaves could not legally marry.

In Winchester, Webb “became a pupil of the famous Carey [sadly unidentified]. The desire for a higher Education was planted in his heart under this pioneer instructor.” Webb then worked his way through State University in Louisville. The school, founded by a convention of black Baptist churches in Kentucky, later became Simmons University. Webb graduated about 1885. That year he was selected to head the colored schools of Winchester, but decided he was unsuited for the job. He then went into the grocery and mercantile business for many years.

In 1879, Webb joined the First Baptist Church in Winchester. He headed a movement in 1889 to organize the Broadway Baptist Church and was its first Sunday School superintendent. About that time, he became president of the largest Sunday School convention in the state of Kentucky and served five years as recording secretary for the Consolidated Baptist Association.

In 1891 he successfully launched his career in journalism and founded the National Chronicle. He sold the paper the following year and went to Indianapolis for four years to continue his editorship.

Webb returned to Winchester in 1896 and married Annie Simms (1862-1923), a school teacher in Louisville. She had the distinction of being the first African-American female delegate to the Kentucky Republican Convention, where she served on the Rules Committee. Annie and Webb had no children.

He continued his journalism career in Winchester, contributing articles to black journals and newspapers. He wrote the “Colored News” column in The Winchester Sun for many years.

Webb enjoyed numerous honors during his career. Gov. J.C.W. Beckham appointed him as one of Kentucky’s special representatives to the 1907 Jamestown Exposition. Webb was active in Kentucky’s Republican Party and was its candidate for U.S. Land Office Recorder in 1891. He made a formal protest before the state legislature on the “separate coach movement,” a proposed state law that would require racial segregation of train passengers. He was a commissioner at the Inter-State Exposition in Raleigh, North Carolina (1908), commissioner to the Emancipation Exhibition in New York (1913), and a delegate to the Half-Century Anniversary Celebration of Negro Freedom in Chicago (1915).

Employment for blacks was extremely limited in Winchester in his day. Census data indicate Webb worked as a janitor or porter for the Elks Club and Citizen’s National Bank for nearly 30 years.

He lived on West Broadway where his parents had preceded him.

Webb died of cancer at a local hospital in 1928 and was buried beside his wife in Winchester Cemetery.

Accolades poured in following his death. Examples include “honored citizen, well beloved by all,” “Winchester suffers the loss of a most distinguished character,” and “his place in this community cannot be easily filled.” The new editor of the “Colored News” headed his column “A King in Israel Has Fallen.”

Following his death, Webb delivered a final surprise: He left an estate of about $10,000. Having no children or siblings, his will designated $200 to Winchester Cemetery for the upkeep of his family lot; the remainder he left to his alma mater to establish the “Banks Ministerial Relief Fund” in order to perpetuate the memory of his father and mother.